The 50th annual conference of the Mormon History Association convened in Provo, Utah, June 4-7. Some 190 scholars and presenters participated in scores of deliveries of various aspects of Mormon history.

Much of the conference focused on the memory of founding member Leonard J. Arrington, who helped form the association in 1965. He was Church Historian from 1972-82.

Following are reports of selected presentations given at the conference.

PROVO, UTAH

The Mormon tradition has impacted art in Utah in a very powerful way, declared Rita R. Wright, director of the Springville Art Museum, as she introduced a session of the conference dealing with that museum, which is in a neighboring city to Provo.

Three presenters in the session dealt with prominent individuals in that Mormon artist tradition.

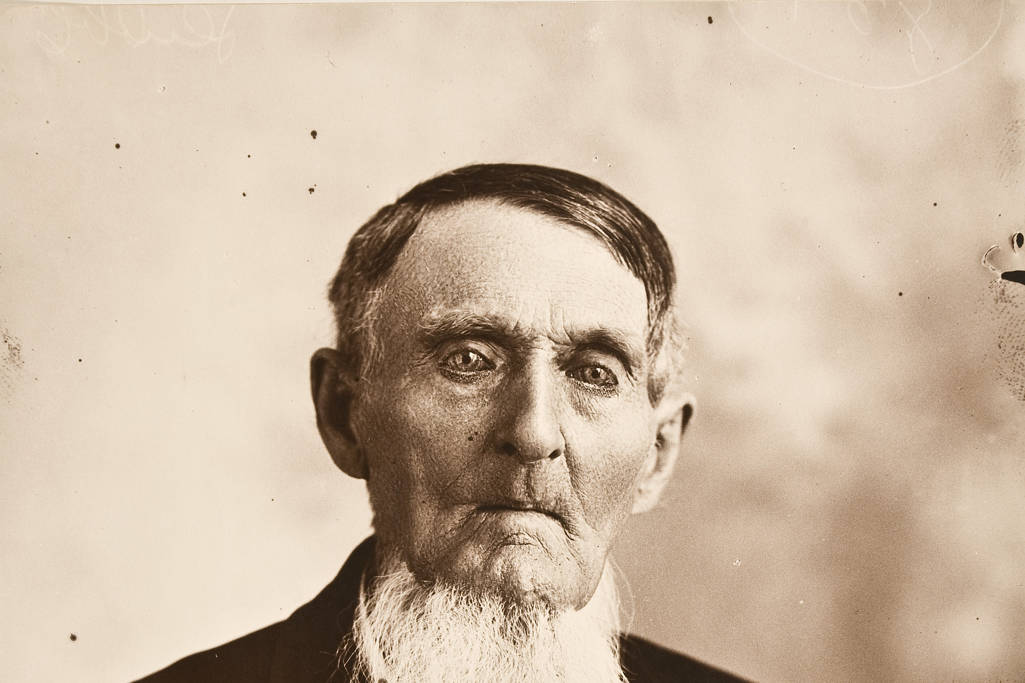

Philo Dibble

Philo Dibble’s dream of an art gallery in Zion began with a personal tragedy: the martyrdom of his friends Joseph and Hyrum Smith on June 27, 1844, said Devan Jensen, executive editor of the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University and a fourth-great-grandson of Brother Dibble.

In July of that year, Brother Dibble had a dream in which he and others were standing under a tree. “I looked and saw Brother Joseph coming with a sheet of paper in his hand,” he recorded. “The paper was rolled up. Joseph threw the roll into the top of the tree. The roll came tumbling down through the limbs, and all under the tree watched the roll to catch it, and I caught it. This was the end of my dream.”

Brother Jensen explained that Brother Dibble “felt that the sheet symbolized a canvas on which scenes of Church history would be painted by various artists. Being poor, he told Brigham Young of his plan. Brigham said, ‘Go ahead, and I will assist you.’

Brigham Young then gave $2 to Brother Dibble, who then went and bought the canvas.

“This donation launched a panorama of Church history events that others would later emulate,” Brother Jensen recounted.

He explained, “Panoramas were popular, much like today’s motion pictures. Panoramas were being displayed in nearby St. Louis.” In fact, that city 200 miles downriver, was a major center for panorama production in America.

About a month after the martyrdom, Brother Jensen said, George Cannon (not to be confused with apostle George Q. Cannon) who had made death masks of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, died of heat stroke, and Brother Dibble obtained those masks. Over the next 41 years, he would protect and display them, often testifying of his firsthand experience with the Prophet Joseph and Hyrum, for whom he served as a bodyguard.

Brother Dibble obtained copyrights on a series of wall-size murals depicting the Prophet’s last speech to the citizens of Nauvoo, the assassination and the display of the bodies. He hoped to eventually include other scenes from the Church’s history. Not being an artist himself, he commissioned friends to do the murals and LDS art.

“Unfortunately, mob action in the Nauvoo area disrupted the mural project,” Brother Jensen said. The Dibble family eventually was driven to Winter Quarters, Nebraska, the temporary settlement of Church members who had been driven from Nauvoo. He showed the paintings there and across the Missouri River in the Log Tabernacle at Council Bluffs, Iowa, on April 7, 1848.

Apostle Wilford Woodruff wrote glowingly of the exhibition. “As Brother Dibble has been moved upon to set up these paintings, I feel to bid him Godspeed; and if he will get up the sceneries of this Church, commencing at the beginning and go through it until now onward and fit up a gallery in Zion, it will be the continuation of the rise and progress of the Church and kingdom of God in this last dispensation, and it will form one of the most interesting sceneries that can be found in Zion.”

Brother Dibble never fulfilled his intention to add many other murals to the panorama, but in 1862, a third painting was added, depicting the Mormon Battalion’s “Battle of the Bulls.” LDS Art

He did travel with his panorama to Mormon communities such as Spanish Fork and Springville, where he settled. His presentation was a kind of traveling museum, and he charged a modest fee for people to see the art and other artifacts such as the death masks, Brother Jensen said. “Over the years, he held many exhibitions in the county, particularly in his home, which was essentially the first Springville Gallery of Art.”

He said Philo Dibble’s efforts inspired other artists, such as Cyrus Dallin who, as a boy of 12, was inspired to begin sculpting when he viewed the death masks of Joseph and Hyrum. In adulthood, he would sculpt the angel Moroni statue for the Salt Lake Temple and the Brigham Young monument at Main and South Temple streets in downtown Salt Lake City.

And other artists improved on the early primitive techniques in Brother Dibble’s murals, Brother Jensen said. “For example, Danish artist C. C. A. Christensen and Norwegian artist Dan Weggeland teamed up to create a small panorama with scenes from the Bible and the Book of Mormon. Christensen later created his own panorama of Church history.”

C. C. A. Christensen

Brother Christensen’s “Mormon Panorama,” currently on exhibit at the BYU Museum of Art, was featured in a cover and center-spread article in the May 31 LDS Church News. LDS Art

Brother Christensen had been a handcart pioneer. He settled in Mount Pleasant in southern Utah’s Sanpete Valley and supported his family through farming, although painting was his first love, and he made nearly as much money from a painting career as he did from his 15-acre farm.

The exhibition at BYU is the first showing of the complete panorama in 10 years, said Paul Anderson, a curator at the Museum of Art who gave a presentation at the Mormon History Association Conference.

He said Brother Christensen in 1850 encountered some of the first Mormon missionaries to Denmark and was baptized. He became a missionary and Church leader in Denmark and Norway in 1853 before immigrating to Utah in 1857. He returned as a missionary in 1865-1868.

In the 1870s, after his return to Utah, he was commissioned to paint a series of 11 small pictures to use in teaching Native Americans about the sacred history of their ancestors, including scenes from the Bible and Book of Mormon, and ending with Joseph Smith receiving the gold plates.

Completed in 1878, the paintings were sewn together in a scroll, which was hung from a frame and rolled vertically to show one picture at a time to illustrate a lecture. The method of presentation was similar to larger panoramas that were common at the time in America.

About this time, he “saw the possibility of making a much larger panorama of the same type to narrate the founding events of the Mormon Church,” Brother Anderson said. “He recognized that the older generation who had lived through these experiences were beginning to pass away. The time was almost gone to do it. Hoping to inspire the rising generations of Latter-day Saints with the power of their religious heritage, he painted 23 dramatic LDS Art scenes of early Church history.”

He based his work on accounts from early Church members who had been eyewitnesses to the events.

“It was a monumental work, each picture measuring 6½ feet tall and 10 feet wide, stitched together vertically, he said. “The painted canvases formed a scroll 175 feet long.”

The scroll was attached to two wooden rods supported on poles, and green curtains hung on the sides to make it look like a stage. The audience at each presentation participated by singing familiar hymns at appropriate intervals.

The first seven scenes were completed in 1879, and Brother Christensen began traveling with the panorama. The last painting was finished by 1890, completing the narrative from Joseph Smith’s First Vision to the arrival of the pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley.

“The energy and dedication required for such an ambitious undertaking rank among the great stories of 19th century LDS art,” Brother Anderson said.

John Hafen

Vern Swanson, former director at the Springville Museum of Art, spoke on the LDS art movement in that town inspired by the message of John Hafen, recognized as one of Utah’s finest landscape painters.

From that movement sprang the Springville High School Art Gallery, which eventually developed into the Springville Museum of Art, he said.

The movement in Springville in turn inspired America’s art in the school movement, influenced by the Springville High School model.